The Leaky Bucket of Female Talent in the Indian IT Industry

Faculty Contributor : Vasanthi Srinivasan, Associate Professor

Student Contributor : Monisha Nakra

One of the key challenges confronting organizations is to improve the talent pipeline of women in the organization. Anecdotal evidence from the IT industry in India appears to suggest that a number of women software professionals drop out in the early stages of their careers. This study was an attempt to understand the factors that would impact the career persistence of women software professionals. How do women professionals in the software services sector in India perceive their careers in the context of 'Self', 'Family' and 'Society'? This article reveals that Self-related social and structural factors play a significant role in the leakage of female talent in the Indian software services industry. The article presents the findings from an empirical study conducted on 190 women working in various software services organizations in the India.

The Indian IT revolution heralded a new era in the organized labour market of the country. In the last two decades, with the proliferation of jobs in the field of IT/ITES, more and more women have entered the workforce at entry level positions. NASSCOM estimates that approximately 30 percent of the employees of IT/ITES organizations are composed of women 1. However, there is a disproportionate representation when it comes to middle and senior management in all IT firms. This depletion of the talent pipeline of women employees in IT/ITES firms seems to reflect the global phenomena of fewer women at senior levels in corporations. Various studies have found that the leakage of female talent takes place in the early stages of their career where women have to juggle various familial roles and responsibilities and professional demands. Globally, organizations are strategizing about gender inclusivity and building a pipeline of female talent in the middle and senior management levels. In this context, it is interesting to examine the software services sector and the factors that affect women’s persistence in IT careers.

Characteristics of the Indian Software Services Sector

The characteristics of the software services industry in India and the nature of its work pose some unique challenges for professionals in the industry, especially for women. The organizations in the software industry in India are project based and as the industry has matured, more complex and strategic projects have been outsourced to India2. This requires a strong operational and delivery focus in a 24/7 environment. This creates pressure on software professionals to work longer hours3 .

This pressure is an outcome of two factors. Firstly, the time differences with the US and Europe which are the dominant trade partners in the industry, which necessitate employees to work evenings in India and maintain the concept of a 24-hour knowledge factory. Secondly, the project orientation of the industry, with rapid technology changes that make skills quickly obsolete, requires software professionals to frequently re-skill. Consequently, software professionals need to put in extra training and educational hours to keep up with these changes 4 . Those women who aspire to play a bigger role in technology need to maintain a consistently high learning curve. The time required for professional development will have to come out of personal time of the employees. Long working hours, unpredictable workloads and the constant pressure of updating skills have a negative impact on work-family balance.

The nature of the industry and the fact that most women software professionals are in ‘the crucial phase in women’s lives’ i.e. 23-38 years, where women are drawn into marriage and motherhood, put increasing pressure on maintaining a work–life balance5 . In a transitioning society like India, where traditionally a woman’s role is redefined in relation to herself, her family and society, the new and expanded role of women with a strong occupational identity is putting pressure on their persistence with their careers.

Given this context, if organizations need to strengthen their talent pipeline of women within the organization, there is a need to ensure that more women to remain in the workforce. Only if significant number of women persisted in the workforce through the early career stages, would the talent pool of senior women leaders in organizations get strengthened.

The objective of the study was to understand the factors that enabled or hindered career persistence in the early career stages of women professionals. Career persistence is defined as the “intent of the women to remain in the workforce and pursue their careers”.

Factors Affecting Career Persistence

We broadly classify the factors affecting career persistence as 'Self', 'Social' and 'Structural' factors. The self-related factors are those that are internal to the respondent – self-perception, career orientation, success definitions, acceptance of social norms and gender roles, proactive and networking-orientation. Social factors are those external factors that closely interact with and influence the respondent – role models, family support system and work-family conflict. Structural factors are those external factors which are not in direct control of the respondent but are defined by the organization where she works – mentorship, interaction with women in the senior management, organizational culture and support systems.

Methodology and Respondent’s Profile

To understand the problem, we conducted an online survey with women software professionals employed in organizations across the country. A survey questionnaire measuring the factors that affect career persistence among women based on existing literature was designed. Apart from this, in-depth interviews with women software professionals were conducted. We administered the survey through the Human Resources departments of various IT organizations.

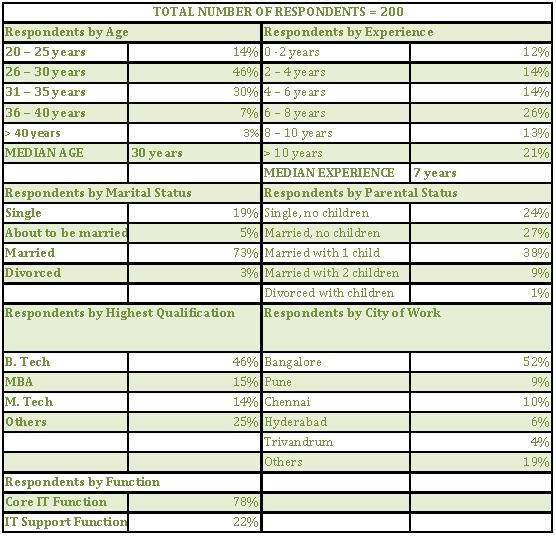

We collected a total of 200 responses over a period of two months and these have formed the sample set for the purpose of this study. The respondents’ profile is shown in Exhibit 1. The median age of this sample of 200 respondents was 30 years and median work experience was 7 years. 73% of the respondents were married and 48% were mothers. Respondents came from a variety of cities – Bangalore had the highest number of respondents, followed by Chennai, Pune, Hyderabad and Trivandrum.

Exhibit 1 Respondent's Profile

Exhibit 1 Respondent's Profile

Survey Results

Some of the key findings of the study are as follows:

Self-Related Factors

More than ninety percent women were emphatic about the fact that their career was a valuable part of their lives and seventy percent agreed that their careers defined who they were. It was not a surprising result given that these women reported that they needed their careers to support their families financially. The degree of gender disadvantage perceived by women was significant – they agreed that at times, they have to work much harder to prove their competence relative to their male peers. A majority of women, especially those married with children, said that they are unable to take up challenging roles that require long hours or extensive travelling. Did women believe in social norms regarding marriage and motherhood? Only half of the respondents agreed that marriage and motherhood complete a woman or that a woman should be the primary caregiver in the family.

However, a majority of women agreed that their career has or would take a backseat to their personal lives at some point. When asked about their definition of success, the respondents frequently mentioned work-life balance and family well-being followed by money and consistent career growth. Pro-activeness and networking are generally considered as strategies through which women can manage their advancement and break through the barriers. This set of respondents categorically believed that the responsibility for the way their career shapes lies primarily with them; seventy percent of them reported that they take initiatives for planning their careers and frequently volunteer for training activities.

Social Factors

Looking at the social factors affecting women, it was interesting to find that fathers and mothers were mentioned equally as role models who influenced women’s choice of career, followed by female friends, female teachers, male friends and sisters. Family support is a very important factor affecting career persistence, ninety percent of our respondents reported a high degree of family support towards their careers and almost the same percentage of married women expressed a high degree of support from their husbands.

Respondents were travelling a distance of twenty-five km on a return trip for work and were working about forty hours a week. When we examined work-family conflict, we found that close to seventy percent women reported that they are not able to spend enough time with their families and likewise found themselves unable to take up enough responsibilities at work. A majority of them expressed feeling some degree of role divergence. Single women indicated that the pressure of getting married is a cause for stress in their lives. However, most of the respondents, both married and single reported a lesser degree of conflict between family and work affecting the other.

Structural Factors

Finally, we look at structural factors that affect women’s careers. Mentorship is widely acknowledged in literature to be a critical factor for women’s careers. Only thirty percent of our respondents were satisfied with the current level of mentorship that they were receiving at their organizations. About forty of them reported having an assigned mentor when they had joined their respective organizations and only about thirty percent reported having a mentor currently. As far as women having access to higher management is concerned, more than eighty-five percent women reported that there were women in the higher management in their organizations. However, only about thirty-five percent reported that they interacted with them twice or more in a year. The respondents vehemently believed that interacting with women in the senior management would be beneficial to their careers.

Looking at support systems provided by organizations, about sixty percent reported that their companies provided support groups for women and young parents and only half believed that they would indeed benefit from joining such groups. About thirty percent reported that their organizations provided child-care facilities and more than eighty percent of the respondents strongly agreed that women in general would benefit from having childcare facilities at work.

Some interesting findings that support the global literature in this field also emerged from the study. We found that belief in gender disadvantage, acceptance of social norms and gender stereotypes have a negative relationship with career persistence. We also found the definition of success in “career” terms to have a positive relationship with persistence. Similarly, both proactive career behaviour and self-definition in adaptive or achiever terms have a positive relationship with persistence. Global literature alludes to career primary and career secondary women. Our study confirms that women who have high proactive career behaviour and define themselves as adaptive or achievement oriented, tend to exhibit career primary characteristics of women professionals.

Another interesting finding pertained to the networking tendency. The data shows a negative correlation between networking and persistence. Literature indicates that networking in organizations would enable women to identify opportunities within the organization that they are otherwise unlikely to gain access too. The counter-intuitive finding requires further investigation. Two reasons could be attributed to this -- women don’t find themselves capable of networking in the manner in which it gives them an opportunity to persist in their careers in organizations or they reject it because they don’t feel comfortable due to the social stigma that may be attached to it, especially in the Indian context. During interactions, several women software professionals expressed that “networking felt like an alien concept to them, they didn’t have the time for it, they’d rather spend their time with their family and kids, and that they can manage just fine without it.” This finding requires further investigation.

Conclusion

With social structures still engendered in emerging economies like India, career persistence as a construct is of immense significance and therefore, women’s likelihood of continuing in their careers is important and requires attention in the research on women’s careers. This study has identified several factors pertaining to beliefs and attitudes about work and family that play a significant role in determining career persistence. Given the rapid growth of the Indian economy and the subsequent implications in terms of a large number of women entering the workforce, this study is an exploratory attempt to address the larger canvass of improving women’s participation, engagement and growth in the workforce.

Keywords

Organisation Behaviour & Human Resources, IT, Women, Careers, Persistence

Contributors

Vasanthi Srinivasan is an Associate Professor in the area of Organizational Behaviour and Human Resources Management, Indian Institute of Management Bangalore. She holds a FPM from IIM Bangalore. She can be reached at

vasanthi@iimb.ernet.in.

Monisha Nakra (PGP 2009-11) holds a B.Tech from MNNIT, Allahabad and can be reached at

monisha.nakra09@iimb.ernet.in .

References

-

Nasscom (2009) Gender Inclusivity in India: Building empowered organizations

-

Ethiraj, S.K., Kale, P., Krishnan, M.S. & Singh, J.V. 2005. Where do capabilities come from and how do they matter? A case in the software services industry”, Strategic Management Journal, 26 (1), pp. 25-45

-

Scholarios, D., & Marks, A. 2004. “Work-life balance and the software worker”, Human Resource Management Journal, 14 (2), pp.54-75

-

Armstrong, D.J., Riemenschneider, C.K., Allen, M.J. & Reid, M.F. 2007. Advancement, voluntary turnover and women in IT: A cognitive study of work–family conflict, Information & Management 44, pp. 142–153

-

Perrons, D. (2003). “The new economy and the work–life balance: Conceptual explorations and a case study of new media”, Gender, Work and Organization, 10(1), pp.65-93