Operations Management in Indian Judiciary: Tapping the Potential

Faculty Contributors : Janat Shah, Professor and Anil B. Suraj, Visiting Faculty

Student Contributors : Mayank Jha and Vernon Fernandez

Indian Judiciary is often associated with inefficiency, corruption and ineffectiveness. The article presents a new approach by studying the judicial system as an operations process. The study depicts how operations management can find applications away from its traditional manufacturing paradigm and how it can be used to build a model that very closely simulates real life flow of cases through the judiciary. Such an approach can provide quantifiable solutions with a focus on areas where they can be most effective. The research generated a series of implementable suggestions that were tested using the model for their impact on the judiciary.

Much has been talked about the delay in rendering justice in the Indian judiciary. As of 2007, there are over 30 million cases pending in the courts of India1 . Such is the extent of pendency that the High Court of Delhi could take up to 466 years to clear out its enormous backlog2 . In India, on an average, it takes about 2.9 years to clear a civil case, with a standard deviation of 2.5 years3 . Pending cases not only indicate the inefficiency of the judiciary, but also lead to huge economic costs for the nation. The delay in justice being served defeats the purpose of the establishment of remedial systems, causing the citizens to lose faith in the system.

A survey of existing literature about court congestion in India reveals that the problem is recognized, but the approach to the issue has been driven by macro-level data. The suggestions in these studies include increasing number of judges, increasing courtrooms, reducing frivolous cases, inclusion of IT, etc. but the solutions are rather qualitative and their impact has not been analyzed.

This study is aimed at analyzing the judiciary as an operations process, using operations management concepts of process flow and system capacity, with the objective of coming up with quantifiable and implementable recommendations which lead to:

- Reduction in case loads (reducing WIP), and

- Quicker movement of cases (increasing throughput)

Methodology

The movement of a case through the court can be viewed as an operations process – similar to pizza making – that involves a series of processes at the end of which an output (judgment) is delivered. However, judicial processes are different in that they may involve different processes for different cases, a high variability at each process step and may involve repetition of processes - all depending on the complexity of the case. Hence, one can be assured of a pizza being delivered in 30 minutes but cannot be sure if justice would be delivered to him even in 30 years!

To build a predictive simulation model while incorporating this complexity, we limited the scope to civil cases in lower courts, as they are more process driven and form a bulk of the cases (over 90% of cases are filed in lower courts). Reasonable assumptions – like steady state and judge being the bottleneck in judicial system – were made. Quality of judgment was assumed constant, which would create an inherent variability in the process and hence it is assumed that no compromise on quality would be entertained.

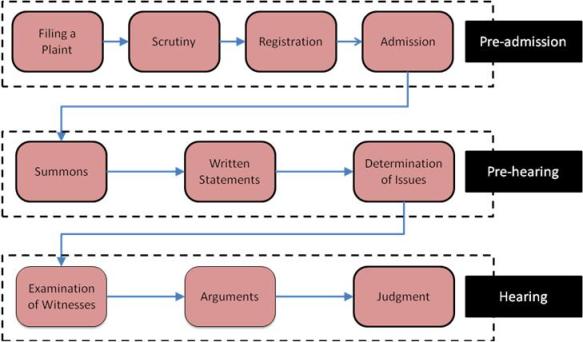

The study analyzed the system from both a process and resource point of view - studying time taken at each process and the way resources were utilized. The judicial process can be simplified in three stages – pre-admission, pre-hearing and hearing. Each stage constitutes of a series of processes steps, adding up to 10 basic steps (see Exhibit 1). The cases can get repeated at any process step, or can be transferred to another step, or can move out (dismissed, sent for interlocutory appeals or settled). Law guidelines were studied and interviews with judges, lawyers and other professionals were conducted to determine time taken at each step and its range of variability.

Exhibit 1 Court case flow process

Exhibit 1 Court case flow process

We developed an analytical model to simulate court processes. The model incorporated basic process flow and built in variability such as range of time taken at every step, possibility of repetition, dismissal, settlement and interlocutory appeals. Using the number of cases and number of judges as an input, the model had the ability to predict total number of cases pending in the system, case load at each step, flow rates at each step, amount of time spent by judges (cumulative and at every step), courtroom load and a distribution range for each of these variables. Further, the system variables (such as timings, range, number of repetitions and percentage transfers) could be modified to study the impact on the output variables.

Observations

The analytical model was built using estimated data obtained through interviews with members from the legal profession. Through these estimates, the model gave a figure of total pendency, which was within 15% of the recorded value of 560,000 cases pending in courts of Karnataka. This validated the model that could be used to gain valuable insights into the judicial process. The model accuracy can be further improved by gaining access to court timings, which is being recorded but is currently unused.

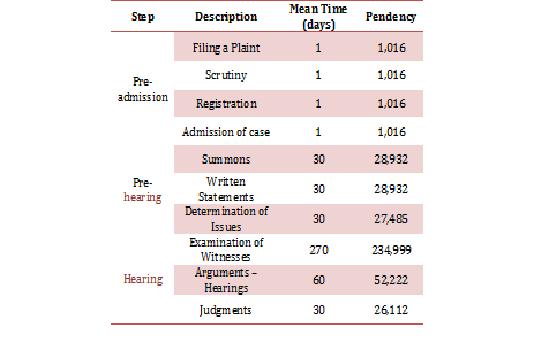

The model generated a split up of the pendency figures for each step, as shown in Exhibit 2.

Exhibit 2 Estimated Pendency at each step

Exhibit 2 Estimated Pendency at each step

As can be clearly seen, the pendency in the system is in direct relation to the amount of time taken to complete that step. When seen from an operations point of view, this is obvious, since a process step that takes more time to complete will have an increased amount of WIP present. All manufacturing systems have a certain amount of WIP inherent in the system, and this level of WIP is necessary to maintain a smooth flow. We determined that over half of the existing pendency is inherent to the judicial system, and cannot be removed under present timings at each step. Thus, the reported problem of a huge amount of pendency is exaggerated, and hence only about half of the existing pendency is ‘unhealthy’.

The model was also able to calculate the amount of time spent by the judges on the cases present in the courts. The model predicted that the civil judges in Karnataka work almost 83 hours a week. This number might seem very high when seen against in-court time, but one must consider that passing judgment and deciding upon a case often happens outside the court. Judges use out-of-court time to review the arguments and evidence in each case, refer to previous judgments on similar cases, write up judgments and keep up-to-date on the latest rulings of the Supreme Court. All-in-all, judges work almost the same amount as investment bankers, and certainly not for the same compensation!

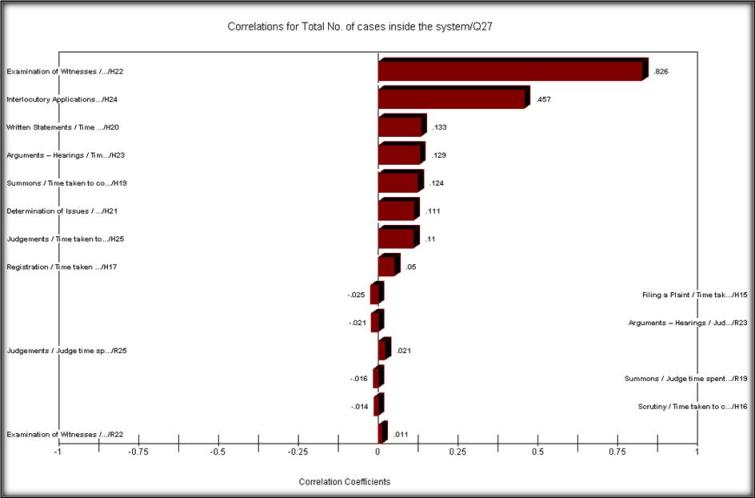

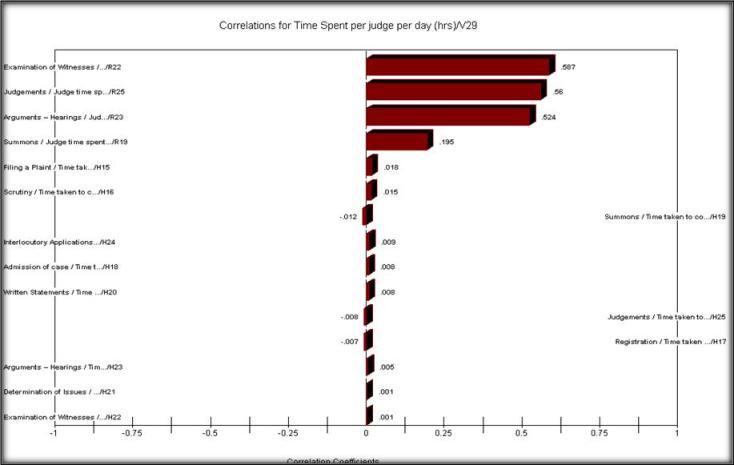

Using the correlation graphs shown in Exhibit 3a and 3b, it is easy to observe that while caseload (pendency) is highly dependent on those steps that take the most time, judge load is dependent on steps of Arguments, Hearing and Judgment, and the number of repetitions. Thus, pendency and judge load are separate issues and can be dealt with separately.

Exhibit 3a Correlation for Total Number of Cases inside the System

Exhibit 3a Correlation for Total Number of Cases inside the System

Exhibit 3b Correlation for Time Spent per judge per day

Exhibit 3b Correlation for Time Spent per judge per day

Recommendations

To generate viable recommendations for the judicial system, we considered a two-pronged approach. First, there was a need to increase the supply of capacity. Second, the various methods to reduce the inputs to the judiciary were explored. These solutions can be analogous to reducing the inventory by increasing the available capacity of a machine, and at the same time, reducing the demand on it. Together, these methods should help rid the system of the excess pendency and result in a judiciary with a healthy, time-bound movement of cases through it.

On the supply side, the model was used to find what increase in judge strength would clear the pendency. It was found that an increase in judge strength of 22% over the existing number of judges would clear the unhealthy pendency within 5 years. Since the current vacancy in judge strength in Karnataka is 26%, we feel that the judicial system must make every attempt to fill this gap. The judiciary could invite retired judges to return to duty to deal with those cases pending over a long time. Even if they work only on weekends, these judges could help reduce the pendency greatly.

As indicated above, the pendency at a step is in direct relation to the time taken by it. Certain process steps have delays introduced due to inefficiency caused by bureaucracy and bribery. Certain other processes are governed by archaic practices that lead to unnecessary time delays. To speed up the process and reduce pendency, these steps in the system could be modernized or even outsourced. For example, using email to serve summons or call witnesses will greatly reduce the time taken at these process steps. Standardizing the process of filing and making it computerized should also improve court records and speed up the system.

The process by which a case continues through the system gave rise to an observation – cases take much more time in the hearing stage rather than the pre-hearing or pre-admission stages. In addition, the judge time spent is almost negligible in the pre-admission stage, but very great in the hearing stage. Hence, if the number of cases passing through the admission process can be reduced, the load on the system (both caseload and judge load) will be greatly reduced.

By moving more cases out of the judicial process into mediation or arbitration, the judiciary can remove frivolous, simple or repetitive cases from the system. If the number of cases passing though the admission stage could decrease by 5%, the total time saved for the judge per day would be 6%. However, if this decrease in number of cases was achieved at the determination of issues stage, only a 4% reduction would be achieved. Hence a practice of ‘move out cases as early as possible’ should be followed.

In order to reduce the corruption in the system, a series of performance measures could be instituted for the court administrative staff. These performance metrics could be generated by using the model to estimate the ideal range of pendency that each process step should involve, similar to process controls in manufacturing. The appointment of a court manager to both oversee this performance benchmarking and take over all the managerial duties from the judges could be a possible solution.

The model was built with a limited scope: only the lower civil courts of Karnataka state were included in the study. However, there is no reason why the study cannot be extended to courts higher up in the chain, across the country and even criminal courts. With the data from the records maintained by every court, the model can be made as accurate as being able to predict when a particular case would be scheduled.

Conclusion

The new approach to view Indian Judiciary as an operations process revealed that Operations Management can add significant value in areas far away from manufacturing. Operational modeling of court processes can provide valuable insights, throw light on the bottlenecks, and suggest areas of improvement.

Such a study of the Indian Judiciary suggests that the system is not “beyond redemption" and there is hope for improvement. Operationally, there are two major problems – the pendency of cases and the overloading of judges. An analytical model can be built to generate simulations which show where the problem lies and how the problems can be resolved. Suggestions for improvement can be tested for their impact on such models. This study can be further extended to criminal cases, higher courts, different geographies and other resources like administrative staff and courtrooms.

Contributors

Janat Shah is a Professor in the Production and Operations Management Area at IIM Bangalore. He holds a Ph. D. from IIM Ahmedabad and a B.E. in Mechanical Engineering from IIT Bombay. He can be reached at janat@iimb.ernet.in

Anil B. Suraj is a Visiting Faculty at the Centre of Public Policy at IIM Bangalore. He holds a Ph. D., LLM and B.A.LLB from National Law School of India University, Bangalore. He can be reached at absuraj@iimb.ernet.in

Mayank Jha (PGP 2008-10) holds a B. Tech from Indian Institute of Technology Bombay and can be reached at mayank.jha08@iimb.ernet.in

Vernon Fernandez (PGP 2008-10) holds a B.E. from Birla Institute of Technology and Science, Pilani and can be reached at vernon.fernandez08@iimb.ernet.in

Keywords

Operations Management, Process Control, Judiciary, Public systems, Courts, India

References

1 Indo Asian News Service, 2007, “Nearly 30 million cases pending in courts – Hindustan Times”, http://www.hindustantimes.com/News-Feed/india/Nearly-30-million-cases-pending-in-courts/266073/Article1-224578.aspx, last accessed on Dec 30, 2009.

2 Dolnick, Sam, 2009, “Report: Indian Court Is 466 Years Behind Schedule”, http://www.law.com/jsp/law/international/LawArticleIntl.jsp?id=1202428286985, last accessed on Dec 30, 2009.

3 Calculated from IndiaStat database