Achieving Universal Primary Education: A Collaborative Model

Faculty Contributor : Trilochan Sastry, Professor

Student Contributors : Ankita Agarwal and Ayesha Jaggi

This article seeks to highlight the key issues and unaddressed need gaps currently impeding the realisation of the goal of universal primary education in India. On the one hand, it highlights the considerable success achieved in certain areas like enrolment and infrastructure and on the other hand, it seeks to find a solution to the biggest threat: ensuring quality learning. From the analysis conducted, follows a collaborative model wherein the private sector, non-governmental organisations (NGOs), the government and the community should work together,towards "Education for All".

The role of education in fuelling and sustaining the growth of the Indian economy cannot be stressed upon enough. It is of paramount importance that the government and other stakeholders take up the mantle of ensuring quality learning and realise the importance of education in the upbringing of every child in the future growth of the country.

While the NGOs have the requisite management abilities and expertise, best practices and the passion and willingness to make a difference, the government has the requisite funds, scale and reach. To date, both NGOs and the government, having worked in their own watertight compartments, have achieved what is individually possible. The challenges of the future will require a partnership and a need to leverage individual strengths to find innovative solutions.

The Current State of Education in India1

To begin to appreciate the education scenario in India and the difficulties in imparting education, it is important to begin with some key statistics. About 80% of all schools in India are government schools; on an average about 95% of the schools have less than 10 teachers with enrolment rates in private schools being roughly half (~43%) that of government schools. However, despite these dismal figures there is a silver lining: there seems to be an observable relationship between the commitments, support and funding provided by the state government; take a state like Kerala for instance. Also contrary to popular belief, a thrust on education from the government boosts enrolment in both public as well as private schools, dispelling the common myth that private schools substitute or will substitute public schools.

Within the education space, certain weak pockets exist across four dimensions: states or region, gender, caste or community and other parameters like children with disabilities or those with special needs. Thus, a Dalit or Muslim girl in North India from a low-income rural family will be among the most disadvantaged when it comes to education. It is also exactly these sections that need education the most to end their exploitation and uplift them from poverty.

Present Day Government Schemes and Initiatives

At present several government schemes and initiatives exist. These are in fact a corroboration of a growing civil movement, which has also culminated in a realisation of the government’s responsibility and recognition of the right to education as a fundamental right.

The Right to Education (RTE) Act2 passed by the Parliament in August 2009 provides a justiciable legal framework entitling all children between the ages of 6-14 years access to quality education on the principles of equity and non-discrimination. However, since the Central Government has only provided the model with each state free to implement the RTE as they desire, the effectiveness has been limited with several implementation issues.

To support the RTE, other initiatives undertaken include the Sarva Shikshya Abhiyan (SSA)3 (to open new schools in habitations, which do not have facilities, and to strengthen existing infrastructure), the Mid Day Meal Scheme4 (the largest school feeding programme to encourage enrolment and attendance in schools and provide adequate nutrition for the child’s development) and setting up of the National University of Education Planning and Administration (NUEPA) (which has created the District Information System for Education (DISE) Database which helps in assessing the progress made on the ground through facts and figures).

The Education Lifecycle or Funnel - Building Blocks to Quality Learning

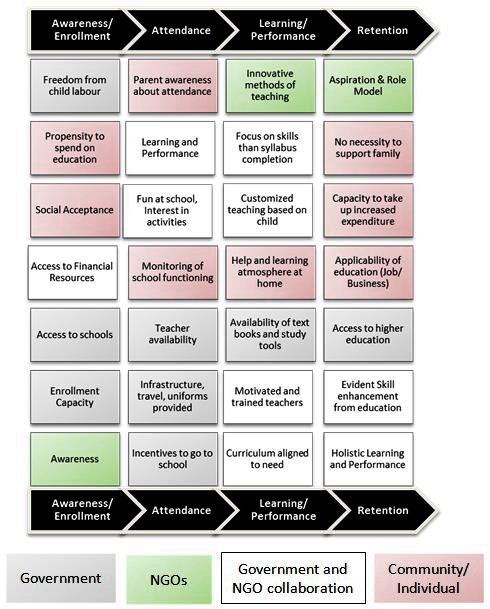

We represent the entire education lifecycle as follows(Exhibit 1):

Exhibit 1 The education funnel or life cycle

Exhibit 1 The education funnel or life cycle

For a long time the greatest challenge was awareness5, but today parents are willing to send their children to school and have realised the importance of education. Thus, the bottleneck has now shifted out to ensuring regular attendance and learning. Attendance driven by the infrastructure, teacher quality and available facilities is an important link between enrolmentand learning/performance. The abstract nature of learning and difficulty of its measurement has very often left this essential step neglected but a recalibration and redesign of the course curriculum to suit every child’s need can ensure good performance and lower dropouts. Finally, retention together with good performance encourages parents and children alike to see the merit in going to school.

Current Challenges - Governmental and Societal

The government can be questioned on its failures6 in terms of providing infrastructure and facilities, skilled and motivated teachers, timely management and monitoring, curriculum creation, focus on incorrect evaluation metrics (i.e. enrolment and not extent of learning) and inequity of education. However, the government also faces severe challenges such as the fragmented population and scarcity of quality teaching resources together with having to manage a large scale and multi grade and multi-level learning.

These are mammoth challenges and coupled with societal challenges like financial constraints, malnutrition of the child, marginalisation and discrimination of certain communities and the girl child and lack of community involvement, we have still come a long way in terms of the progress made thus far. This realisation is essential for appreciating and understanding why we probably could not have been any better off than what we currently are.

NGO Initiatives and a Model for Classification

Several NGOs have sprung up in the last few years and many of them actively work in the education space and are passionate proponents of education reform and policy. We have broadly classified them into five major categories7:

- Funds or Trusts that provide scholarship and interest free loans

- Main Stream Educationists who set up their own schools and institutes differing in ideology and manner of delivering education from existing systems

- After Schools/Pre Schools that provide support to set up the right foundation through preschool and coaching and counselling through after school and remedial classes

- Curriculum Change Consultants that work hand in hand with the government by improving curriculum and teaching in existing government schools

- Community Model wherein the NGO is a facilitator guiding the community to build a model sustained by community resources

While NGOs have been successful in providing grassroots level education, it has only been in small numbers and with limited coverage. Many a times they present an exemplified view of their achievements and are sometimes far removed from ground realities. Most NGOs work in silos and are averse to adopting models developed by others. Those supported by private donors and agencies spend much of their time and resources in garnering funds. Most importantly, NGOs suffer from the inability to scale up either due to constraints of finances or limitations of the model adopted by them.

A Collaborative Model - Government and NGO Partnership

To date, the focus of the government was improving enrolment numbers while NGOs focused largely on learning and quality of education. Thus, there was a divergence in the issues addressed by the two. The lack of trust between the two further inhibited any partnership. However, going forward the best solution is working together. The private players will never have the incentive or scale to reach the farthest corners of the country and the government cannot absolve its responsibility of providing education. Leveraging the strengths of both stakeholders with a focus on the learning of the child will yield far superior results and greater success.

Why Collaborate? A Need Gap Analysis Explanation

A collaborative model as the answer may not seem intuitive at first, but a need gap analysis makes the answer obvious. We have developed the following two grids to simplify this analysis and draw significant conclusions in proposing a solution.

On the education funnel,we identified the key factors needed to ensure successful achievement of a particular step. The grid has been coded in two ways.In the first instance it classifies the factors based on criticality of the problem and ease of resolution (Exhibit 2).

Exhibit 2 Classification of factors based on criticality of the problem and stage or resolution

Exhibit 2 Classification of factors based on criticality of the problem and stage or resolution

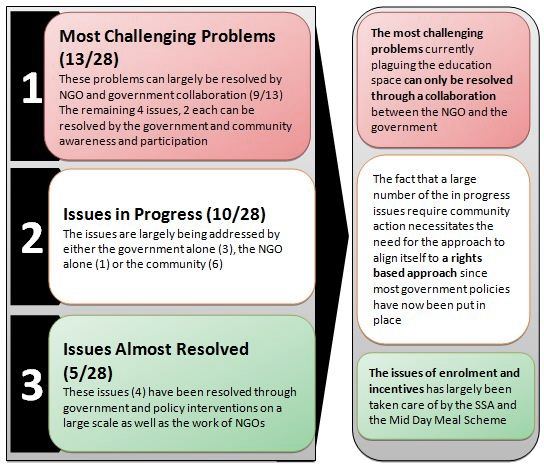

In the second instance the grid classifies the issues based on who should take responsibility for resolving them (Exhibit 3).

Exhibit 3 Classification of issues based on responsibility by stakeholders

Exhibit 3 Classification of issues based on responsibility by stakeholders

Mapping the two grids together,we classified the issues into three broad categories: most challenging, in progress and almost resolved. We also assigned responsibilities in addressing the issues to different stakeholders and deduced that addressing the most critical aspects is only possible through collaboration between the government and the NGOs. The Exhibit 4 below summarizes the key insights.

Exhibit 4 Mapping of issues and the stakeholders

Exhibit 4 Mapping of issues and the stakeholders

Key Aspects of the Proposed Partnership

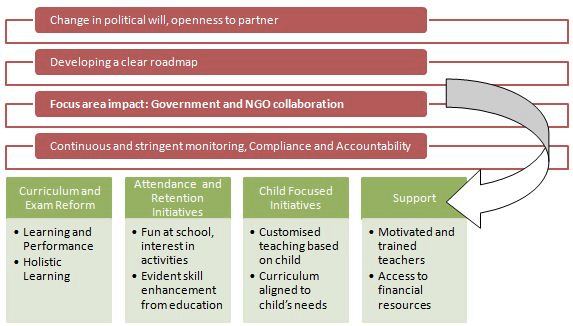

Developing a partnership entails a change in the political will and ideology of government departments, developing a clear roadmap and partnership criteria together with continuous and stringent monitoring to ensure compliance. The thrust of this partnership should revolve around four focus areas (Exhibit 5).

Exhibit 5 Focus areas of proposed partnership model

Exhibit 5 Focus areas of proposed partnership model

An examination of the proposed solutions throws light on the common principle binding them together: The focus must be on the child rather than the system. Consider any aspect of the present education scenario, a system has been built and all its entities, be it students, teachers or parents are being customised to fit into the system instead of customising the system to fit their needs and aspirations. Exams are common for all students in a particular class and a common grading metric is applied. A key fact not accounted is that though the end of the racing track may be the same for all students, the starting point may be different for every student based on their background and history.

The need of the hour is modular training, aiming at improving learning levels rather than just increasing literacy percentage in the country. The scale and complexity of the task itself justifies the need for more than one stakeholder.

The NGOs must build modules that are self-explanatory and easily replicable in the cobweb of government schools. The basis of the grading system must be progress levels relative to the starting level rather than an absolute grading. Well-tested evaluation tools built by Pratham and the likes can be used for this purpose. The classroom or the grade one belongs to should not bind learning. Additionally, cross-level camps should give every child an equal opportunity to realise his or her potential.

Keeping in mind the background and the needs of the section of society we are looking at, it becomes important for the parents and students to experience instant benefits of schooling for them to sustain their move towards education. Innovative teaching methods crafted by NGO’s can make learning useful and fun. Providing internships to young adults through a government-developed system will further help in creating an awareness of the impact of education. The stipend earned and the test of practicality will strengthen confidence in the system.

Conclusion

Thus, from an overall analysis of the current state of education and the requirements of the future, a collaborative model seems to be the right approach. The government and NGOs must realign their goals and commit themselves to working together.

The country and the future of primary education in India today hinges on the three pillars of: Apeksha: Balancing expectations and aspirations of all, Avashakyta: Recognising the needs of the child, society and the country and Aastha: Living up to the faith the people show in the government and its partners. Together, these will form the foundations of and herald a new education system capable of providing quality education to all.

Keywords

Collaboration, Right to Education, Partnership, Primary Education, Government, Non-Governmental Organisations, Strategy, Public Policy

Contributors

Trilochan Sastry is a Professor in the Quantitative Methods & Information Systems area at IIM Bangalore. He holds a Ph. D.from MIT, USA and an MBA from IIM Ahmedabad, India. He can be reached at

trilochans@iimb.ernet.in.

Ankita Agarwal (PGP 2010-12) holds a B.E from People’s Education Society Institute of Technology (PESIT), Bangalore and can be reached at

ankitaa10@iimb.ernet.in.

Ayesha Jaggi (PGP 2010-12) holds a B.Com (Hons.) from Shri Ram College of Commerce (SRCC), New Delhi and can be reached at

ayeshaj10@iimb.ernet.in.

References

-

National University of Educational Planning and Administration, 2011, "FlashStatistics: Elementary Education in India: Progress towards UEE",Jan 2011, DISE Database and Group Analysis based on available figures, http://www.dise.in/Downloads/Publications/Publications%202009-10/Flash%20Statistics%202009-10.pdf, Last accessed on August 10, 2011

-

Ministry of Human Resource Development, Department of School Education and Literacy, 2010,"RTE Report by Anil Bordia Committee",Apr 2010, http://ssa.nic.in/quality-of-education/rte-reporting-by-anil-bodia-committee, Last accessed on July 22, 2011

-

Ministry of Human Resource Development, Department of School Education and Literacy, 2011,"Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan", http://education.nic.in/ssa/ssa_1.asp, Last accessed on July 22, 2011

-

Ministry of Human Resource Development,Department of School Education and Literacy,2011,"Mid Day Meal Scheme", http://www.education.nic.in/elementary/mdm/index.htm, Last accessed on July 22, 2011

-

The Probe Team, 1999,Public Report on Basic Education in India, New Delhi: Oxford University Press

-

Lal, Meera,"Education- The Inclusive Growth Strategy for the economically and sociallydisadvantaged in the Society",District Information System for Education (DISE) publication, http://www.dise.in/Downloads/Use%20of%20Dise%20Data/Meer%20Lal.pdf, Last accessed on July 22, 2011

-

Primary research through NGOs visits, mail and telephonic correspondences,interviews, in particular with, Mr. Vikas Maniar at Akshara Foundation, Mr. Parth Sarwate at Azim Premji Foundation, Ms. Sindhu Nayak, the teachers and management at VIDYA, Ms. Nikita at Parikrma, Ms. Anupama at CWC, Mr. Arun Kapoor (volunteer) at Aakanksha.